Inside Abu Ghraib: Missed Red Flags, Team Under Stress

- Jonathan Eig

- Nov 23, 2004

- 16 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2022

Originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Nov 23, 2004

Before there was Abu Ghraib, there was Virginia Beach.

In March 2003, shortly before the 372nd Military Police Company of Army reservists shipped out to Iraq, its members enjoyed a weekend of R&R.

Three of the soldiers -- Lynndie England, Charles Graner and Steven Strother -- took off for Virginia Beach, Va., in a borrowed Ford Focus. They got drunk one night, and when Spc. Strother passed out, Spc. England took off her clothes and got in bed with him, according to Spc. Strother's testimony before a military court. He said Cpl. Graner took pictures, and then Spc. England snapped more photos while Cpl. Graner exposed himself next to Spc. Strother's head.

"It was just a joke," Spc. Strother testified.

It was also a hint of worse things to come.

What happened at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq eight months later is now well known as a low point in U.S. military history. Naked detainees were stacked in pyramids, raped with phosphorescent light sticks and forced to masturbate in groups. While all that and more happened, American soldiers smiled for the cameras and signaled their approval with broad grins and hoisted thumbs.

An independent panel headed by former Defense Secretary James Schlesinger assigned direct blame to the soldiers in the prison and their immediate supervisors. The panel also blamed top leaders at the Pentagon. It said interrogation methods used on suspected unlawful combatants at Guantánamo Bay in Cuba, where the Bush administration says the Geneva Convention doesn't apply, were transferred to Iraq, which the Pentagon says is covered by the treaty protecting prisoners. At the same time, many of the controls that were in place at Guantánamo were absent at Abu Ghraib, investigators found.

Intense pressure from high up the chain of command led to overly aggressive tactics, the report concluded. Meanwhile, it said, overwhelmed soldiers in the prison were unclear as to who was in charge and how far they should go to help get information.

Beyond these larger forces, some who were inside Abu Ghraib tell a relatively simple story. They describe how one soldier with a strong personality and red flags in his record apparently triggered a descent into horrific behavior while a distracted Army hierarchy failed to stop it.

The Army Reserves' 372nd Military Police Company is based in Cresaptown, Md., population 6,000. Its civilian members are cops and restaurant managers and salesmen. They come from small towns in Maryland, Pennsylvania and West Virginia, places where coal mines once dominated local economies.

Some joined the reserves because of anger over the Sept. 11 attacks, but most for the money. In peacetime, they might pick up an extra $250 a month, enough for a car payment, and have to serve just one weekend a month plus two weeks of annual summer camp. But with the regular armed services stretched thin by Afghanistan and Iraq, the government has called Army reservists and National Guard members to active duty in large numbers and pressed them into jobs normally done by full-time soldiers.

In 2001, the 372nd was sent to Bosnia for the better part of a year. Not long after getting back, members learned they would leave again, for Iraq. Cracks in morale appeared, as most had never imagined having to spend so much time away from homes and jobs. In February 2003, when the company reported for duty at Fort Lee, Va., some reservists complained that they were too sick to serve. The Army filled the gap with individual soldiers from other reserve units.

A few officers complained that the newcomers upset the company's chemistry. But when Cpl. Graner was brought in, he seemed like a welcome addition.

In his mid-30s, he was a tall, thick-chested veteran of the first Gulf War, with a Marines eagle tattoo on one arm. "His personality was such that he would say, 'Suck it up! We're going!' " says Janis Karpinski, an Army Reserve brigadier general who later headed a brigade that included the 372nd company. Gen. Karpinski, who in civilian life is an executive-training consultant, says the 372nd soon identified Cpl. Graner as someone who might make a strong leader.

A lawyer for Cpl. Graner, Guy Womack, says the military has tried to portray his client as the architect of abuse at Abu Ghraib to distract from organizational failures. He says he'll prove in a court martial early next year that his client was following orders from military intelligence to soften up detainees for interrogation.

A May investigative report by Army Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba concluded that some military-intelligence and other government interrogators "actively requested that MP guards set physical and mental conditions for favorable interrogation of witnesses." Cpl. Graner, according to his lawyer, "is not a ringleader."

Former Marine

After growing up near Pittsburgh, Mr. Graner joined the Marines in 1988, training as an MP. When he got out after the Gulf War, he became a construction worker and then a prison guard, at Fayette County Prison in Pennsylvania and then at a state prison in Greene, Pa.

By the start of his second war in Iraq, much in his life had soured. At the state penitentiary, he was reprimanded three times and suspended four times for showing up late or taking unauthorized leaves, according to a prison official. The official says the prison tried unsuccessfully to fire him.

And his marriage had broken up. Between 1997 and 2001, Cpl. Graner's then-wife obtained three orders of protection against him. She accused him in Fayette County court of threatening to kill her and of grabbing her by the hair and trying to throw her down the stairs. Cpl. Graner's lawyer says the allegations were part of a contentious divorce and were groundless. The former wife couldn't be reached for comment.

Cpl. Graner's military file included the allegations, and put him in a class of soldiers not qualified for duty in Iraq, Gen. Karpinski says. But the 372nd was short-handed and trying to get to Iraq as fast as possible. Gen. Karpinski says she doesn't know who cleared him to go.

The soldiers' move to Iraq was delayed. They sat around for several weeks at a base in Virginia. While there, Cpl. Graner found himself drawn to a short, moon-faced woman from West Virginia: Lynndie England.

Just 21 at the time, she, like Cpl. Graner, had a broken marriage. Working the night shift in a chicken-processing plant, she had joined the reserves partly in hopes the Army would help her pay for college, family members told reporters last spring. It was during their wait in Virginia that Cpl. Graner and Spc. England, along with Spc. Strother, had the raucous weekend in Virginia Beach. Photos soon were circulating among soldiers at the company. Cpl. Graner's lawyer said he wasn't familiar with the incident. Spc. England's lawyer didn't return calls.

Because Spc. England's divorce wasn't final, her relationship with Cpl. Graner violated military rules, the corporal's lawyer says. But no one acted firmly to break up the affair for months, Gen. Karpinski says, in part because the company's command was in flux.

Spc. England was a clerk in the office of the company commander, Capt. Donald Reese. "We counseled her a few times," Capt. Reese says, in his first public comments since the scandal erupted last spring. "You see a kid and she's awed by someone a little older. Graner can be a very charming guy. People tend to follow him, whether it's the right way or the wrong way. Still, all you can do is counsel her and say, 'Hey, you're screwing up.' "

First Assignment

In May 2003 the company arrived in al-Hillah, Iraq, south of Baghdad. They found a sprawling city where jails had been emptied, police had quit and looters ran free. Their job was to help the Marines establish order.

The company was housed in an old date factory with no air conditioning and sometimes no power or plumbing. They shared the floor with rats and pigeons, and sewage bubbled up through cracks in the pipes. But morale wasn't bad, because the reservists were doing what they'd been trained to do, as military police. They patrolled by night, chasing looters through alleys and sometimes disarming drunks wielding grenades.

Capt. Reese says Cpl. Graner liked to pull pranks to get under the skin of his superiors. "He would push the first sergeant's button ... Little stuff, just to get him going," the captain says.

One bizarre prank took place when company leaders were holding their daily 5 p.m. meeting. Cpl. Graner walked in on them dressed in a sudsy, soaking-wet uniform and announced he was doing his laundry, according to one of the company leaders, Sgt. Scott Rinehart. He returned a few minutes later, still wet but without the bubbles, and said he was in the drip-dry stage.

Sgt. Rinehart says the corporal, apparently expressing his desire to leave the Army, violated rules by altering his name tag, making it read "DOD [Department of Defense] Civilian."

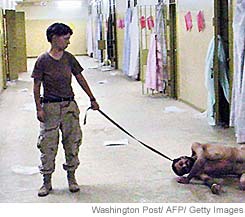

Cpl. Charles Graner with Iraqi prisoner who died at Abu Ghraib.

Cpl. Graner impressed some as an energetic soldier unafraid of confronting the enemy. "Graner was the guy who'd say 'let's go do this' and people would follow. He could lead weak-willed people," Sgt. Rinehart says. Others saw him as a man who disrespected his superiors. In any case, say Capt. Reese and Gen. Karpinski, they saw no reason to expect problems from him or anyone else.

A staff sergeant named Ivan Frederick II allied himself with Cpl. Graner. He, too, was a prison guard at home, in Virginia. Fellow soldiers describe Sgt. Frederick, 38, as an easy-going man who seemed eager to fit in. A lawyer who defended him calls him a person with "a very strong need to please, a very strong need to avoid conflict." According to the lawyer and some soldiers, that passivity played a part in what followed.

'Hard Site'

After several months in Hillah, the MPs were sent to Abu Ghraib, a sprawling, dusty prison near Baghdad ringed with razor wire. It was filling with Iraqi detainees, ranging from petty criminals to former intelligence operatives for Saddam Hussein. Handling them proved a job that shook the confidence of even the company's staunchest optimists.

When they got there, the guards told them that military intelligence officers called most of the shots. Military police weren't used to taking orders from intelligence officers. But there was nothing ordinary about Abu Ghraib.

As MPs, the members of the 372nd had not been trained for prison work. Capt. Reese, whose civilian job is selling window blinds in New Stanton, Pa., had never seen the inside of a prison, he later told Pentagon investigators. Taking over after two weeks of instruction from a departing group of guards, the reservists learned as they went along.

Among areas they were responsible for was Tier 1A, where high-priority detainees were held for interrogation. While most inmates were housed in tents in courtyards, those of Tier 1A were kept in a two-story cinder-block building known as "the hard site." Some of Tier 1A's detainees were naked and shackled to cell bars even before the 372nd got there, according to Pentagon reports and soldiers who were there.

To run the tier, Capt. Reese chose two men who were prison guards at home, Cpl. Graner and Sgt. Frederick. "When you're short on personnel, you take the people who have experience," he says. He wouldn't have given Cpl. Graner such a role if he'd known his full background, he adds.

Gen. Karpinski says she relied largely on Capt. Reese to tell her what was going on in Abu Ghraib. The captain says that he, in turn, relied partly on a platoon leader supervising the hard site, Capt. Christopher Brinson.

The prison's population ballooned to nearly 7,000. From outside, insurgents pummeled it with mortars. Abu Ghraib had a hellish reputation under the Hussein regime as a place of torture and execution. To the Americans it was a different kind of hell: cold, cramped and full of detainees prone to riot. Some soldiers felt like prisoners themselves.

Those assigned to Tier 1A worked in a particular dank place, rotten with the smell of feces and body odor. Yet in some ways they were more fortunate, working in a strong building and handling only about 50 detainees. Those on the night shift operated with little oversight.

'Softening Up' Detainees

Some soldiers in the outdoor compound resent the notion that prison conditions incited the Tier 1A guards' abuse. It didn't happen in the outdoor area that housed prisoners in tents, says Sgt. Rinehart, despite "times when we had ungodly amounts of stress." He controlled his detainees by giving and taking away privileges such as cigarettes, slippers and food. If members of his platoon lost their composure, he sent them to work in guard towers until they calmed down.

The Army's Taguba report said MPs in the hard site had been told that intelligence officers wanted its detainees "softened up" so they would talk. How much that had to do with the abuse has been the subject of much debate.

The attorney for Cpl. Graner says his client was a dutiful soldier applauded for his work. He cites a congratulatory memo from Capt. Brinson that read in part: "Cpl. Graner, you are doing a fine job in Tier 1 ... Continue to perform at this level and you will help us succeed at our overall mission." Capt. Brinson, a congressional aide in civilian life, didn't return calls seeking comment.

In charge of military-intelligence interrogation at the prison was Lt. Col. Steven Jordan. In his testimony for the Taguba report, he said he was under pressure to extract information but denied telling MPs to treat detainees roughly, and said he would have stopped the abuse if he'd known of it.

The 372nd company's Capt. Reese says if the soldiers felt pressure to get tough with detainees, it probably came informally, from low-ranking members of military intelligence, and in any case should have been ignored. One military intelligence soldier, Spc. Armin Cruz, has been sentenced to eight months in prison and a dishonorable discharge for his part in the scandal. His attorney, who plans an appeal of the sentence, rejects the notion that intelligence officers initiated the abuse, saying most of those mistreated had no intelligence value.

Capt. Reese says he and other officers checked on the night-shift soldiers at Tier 1A about four times a week. He says they were well behaved when he came around. He says he was later told "they had little signals and everything if somebody was coming down the hallway."

Several members of the company say Cpl. Graner's personality emerged as a strong force in Tier 1A. Sgt. Frederick was the shift's highest-ranking member. Sgt. Javal Davis, also on the night shift, told investigators for the Taguba report that "the soldier in charge of 1A was Cpl. Graner." Sgt. Davis said Cpl. Graner sometimes told others that military intelligence wanted detainees "loosened up."

* * *

In 1973, a psychology professor at Stanford University conducted a famous academic exercise in which students played the role of either prison guard or inmate. The professor, Philip Zimbardo, says that once the "guards" grew acclimated to their work, those with the most aggressive personalities began behaving sadistically -- and then "guards" with more passive personalities followed. Soon, "guards" began abusing "prisoners," and even students who didn't condone the abuse made no effort to stop it.

Sgt. Davis, asked by investigators why he didn't refuse to go along with the abusive conduct at Abu Ghraib and report it, answered with a comment that could have been lifted from the Stanford experiment: "I assumed that if they were doing things out of the ordinary or outside the guidelines, someone would have said something." Sgt. Davis faces a military trial next year. His lawyer plans to argue that his client was following orders from the highest levels of government.

Two women were assigned to the Tier 1A night shift. Spc. Megan Ambuhl, a lab technician from Virginia, who didn't appear in any of the photos, pleaded guilty to dereliction of duty for failing to report the abuse. She was demoted and lost a few weeks' pay. Some fellow soldiers describe her as soft-spoken and under the influence of Cpl. Graner. Her lawyer, Harvey Volzer, calls her "a classic follower" and says, "The bottom line is this is the military, and you listen to your [noncommissioned officer] and you listen to your officers."

Cpl. Charles Graner and Spc. Sabrina Harman with detainees.

Soldiers describe the other woman on the shift, Spc. Sabrina Harman, as tougher and more independent. An assistant manager at a Papa John's Pizza in Virginia, she is the daughter of a homicide detective who sometimes showed the family crime-scene photos, according to the Washington Post. Spc. Harman still faces military charges. Her attorney wouldn't comment on characterizations of her personality or specific allegations but said she was a "minor player."

Of all those caught up in the scandal, Spc. Jeremy Sivits earns the most sympathy from fellow soldiers, some describing him as naive and insecure. Known as Puggs, he was a mechanic who often spent time in the hard site because his job was to maintain the building's generator. "He was just looking for something a little more exciting than the motor pool," says Sgt. Stephen Pierson, a member of the company who wasn't assigned to the Tier 1A night shift. Spc. Sivits didn't return calls seeking comment.

Ms. England wasn't assigned to Tier 1A. But she visited Cpl. Graner there. Indeed, she was demoted to private first class in October 2003 for ignoring warnings to stop coming to that part of Abu Ghraib. This discipline coincided with the first serious effort made to break up the relationship between her and Cpl. Graner, according to Capt. Reese.

He says the corporal also was reprimanded for the relationship, but less severely. "It was more her hanging out with him. He was where he was supposed to be," Capt. Reese says.

Found Dead

The worst of the Abu Ghraib abuses came just weeks after the 372nd arrived at the prison. A detainee named Manadel al-Jamadi was found dead in one of the showers in Tier 1A on Nov. 4, 2003. An unidentified Navy SEAL testified to a military court last month that the suspect had been roughed up by interrogators the night before at another location. Several members of the 372nd, including Cpl. Graner, knelt beside the body and posed with their thumbs in the air.

The cameras kept clicking when the focus moved to living detainees. One night, Sgt. Frederick told the military court, he saw a detainee standing on a box in the shower, with wires dangling nearby. He testified that Cpl. Graner said intelligence officers "wanted him stressed out."

Sgt. Frederick said he wrapped a wire around one of the detainee's fingers, while Sgt. Davis attached a wire to the Iraqi's hand, Spc. Harman attached one to his toe, and someone attached a wire to the detainee's penis. While the naked and hooded prisoner waited, anticipating a jolt, Sgt. Frederick and Spc. Harman snapped pictures with a digital camera. An attorney for Sgt. Davis says that his client denies attaching wires and that other soldiers have given sworn statements clearing his client.

The Taguba report listed more misbehavior, most of it over just a few days in early November 2003: "Breaking chemical lights and pouring the phosphoric liquid on detainees; pouring cold water on naked detainees; beating detainees with a broom handle and a chair; threatening male detainees with rape; allowing a military police guard to stitch the wound of a detainee who was injured after being slammed against the wall in his cell; sodomizing a detainee with a chemical light and perhaps a broomstick; and using military working dogs to frighten and intimidate detainees with threat of attack, and in once instance actually biting" one.

Abu Ghraib detainees questioned by the Army described most MPs by their appearance or uniform, but some knew Cpl. Graner by name. They described him as being at the center of the action, while others stood by taking pictures.

Cpl. Graner, one inmate told the Army, "cuffed my hands with irons behind my back to the metal of the window, to the point my feet were off the ground and I was hanging there for about 5 hours just because I asked about the time, because I wanted to pray. And then they took all my clothes and he took the female underwear and he put it over my head. After he released me from the window, he tied me to my bed until before dawn ... Graner and the other two soldiers were taking pictures of everything they did to me."

The photos weren't part of the softening up, some soldiers later testified, but trophies to show to friends at home. The MPs are smiling in most of the shots.

Pfc. England testified to Pentagon investigators that her participation began when she visited Tier 1A and Cpl. Graner suggested she pose holding a naked detainee on a leash. She said he led the man from his cell and put on the leash, and she stared down at him as Cpl. Graner took a picture. "I did not drag or pull on the leash," she said.

While detainees were being kicked, punched or tossed around, according to Spc. Sivits's testimony to investigators, Cpl. Graner "was joking, laughing, p- off a little bit, acting like he was enjoying it." He said Sgt. Frederick was "same as always, mellow. He was really not saying much. Just kind of standing there."

As for himself, Spc. Sivits said, "I was laughing at some of the stuff they had them do. I was disgusted at some of the stuff as well." Asked why he didn't report the abuse, Spc. Sivits said, "I was asked not to, and I try to be friends with everyone."

'Be Good to Me'

Several MPs who weren't in the Tier 1A say that in hindsight, they should have picked up on clues something was wrong there. Sgt. Rinehart entered the area several times a week to usher detainees in or out. He says he saw naked men handcuffed to cells and heard them complain, but had no idea how badly some were being treated.

Sgt. Rinehart says he made a point of visiting certain detainees on the tier and checking on them. To protect one prisoner, he says, he wrote on his sleeve in magic marker: "BE GOOD TO ME" and signed it R-7, his own radio call signal.

Staff Sgt. John Tamuschy, who worked in Abu Ghraib but not in Tier 1A, doesn't buy the idea that the abusers thought they were following orders. "I think it was one person, and he had the charisma to turn around the others," he says.

Maj. Gen. George Fay, co-author of a second Pentagon report on the prison scandal, says higher officers should have taken precautions to make sure one or two soldiers didn't spoil a whole platoon. He says if Gen. Karpinski knew she had weak people commanding the 372nd company, she should have done something about it. And he says if the company commander, Capt. Reese, knew that Pfc. England and Cpl. Graner were having an affair, he should have acted more forcefully to break it up.

Capt. Reese says he accepts some blame for the abuse but adds that "I don't think I could have stopped it unless I was there every night. And you shouldn't have to be there every night." He remains on active duty in the U.S., unable to go back to his civilian job until the trials are over.

Gen. Karpinski says some soldiers in the company exploited its weak leadership. But she is convinced they wouldn't have behaved as they did without instructions from intelligence officers. She, too, says she accepts some of the blame. She remains a general in the reserves but was suspended from her brigade command.

When the Abu Ghraib photos became public earlier this year, several soldiers quickly confessed. "I was in the wrong...I should have said something," Spc. Sivits said as he pleaded guilty to abuse charges. He was demoted and sentenced to up to a year in prison and a bad-conduct discharge.

Sgt. Frederick drew an eight-year prison sentence for his a guilty plea to multiple charges. "I was wrong about what I did," he said. He was demoted and faces a dishonorable discharge.

Pfc. England is in Fort Bragg, N.C., awaiting trial. In October, she gave birth to a baby boy.

Mr. Graner, his rank switched from corporal to an equivalent specialist rank, faces trial on charges of maltreating prisoners, assault, indecent acts, obstruction of justice, adultery and dereliction of duty. He's being transferred to Fort Hood, Texas, for trial.

His lawyer, Mr. Womack, plans to argue that while his client knew some things he did were questionable, he did them because of orders from military intelligence. Besides the Taguba report's finding that some members of military intelligence asked that MPs set conditions for favorable interrogation, the lawyer cites a photo discovered after the Taguba report came out. He says it shows military intelligence officers present during some of the abuse.

The pyramid of naked Iraqi detainees was "no big deal," according to Mr. Graner's lawyer: "Cheerleaders all across America form pyramids every day, and it doesn't hurt people," he says. "This was a control technique."

He also contends that guards in civilian prisons routinely put collars on inmates' necks. "This was not the result of soldiers becoming sadistic and brutalizing people," the lawyer says. "It was a matter of the intelligence community being under tremendous pressure to produce and get evidence that could be turned into intelligence. I think everything that was done there was perfectly lawful."

His client, Spc. Graner, suffered no moral crises, Mr. Womack adds. "He wasn't ashamed of it. His psyche was fine. He was following orders."

Corrections & Amplifications:

Pennsylvania's State Correctional Institution Greene is located in Greene County. The article above incorrectly said the facility is located in Greene, Pa.

Hôm trước mình tình cờ thấy cái hb88 trong một cuộc trò chuyện trên mạng, nên cũng quyết định vào xem thử cho biết. Mình chỉ lướt qua một chút, không tìm hiểu sâu nhưng thấy bố cục khá ổn, các mục được sắp xếp rõ ràng. Đọc lướt cũng dễ, không bị rối mắt, với mình như vậy là đủ để hiểu sơ qua thông tin cần thiết rồi.

Hôm nọ, mình có lướt qua một vài bài viết và thấy có người nhắc đến fabet, nên mình cũng hơi tò mò và quyết định vào xem thử. Mặc dù không nghiên cứu chi tiết, nhưng mình đã dạo qua một chút để xem cách bố trí và cấu trúc nội dung. Thấy rằng mọi thứ được trình bày khá ngăn nắp, các mục rõ ràng, nên mình dễ dàng nắm bắt thông tin cơ bản mà không bị rối mắt. Cảm giác như vậy là ổn rồi!

I came across https://ea77.lat/ through a few experience-sharing articles and decided to check it out. Although I haven’t spent much time exploring it yet, my initial impression is that the content layout is quite well-organized, with clearly separated sections that make it easy on the eyes.

Mình có lần lướt đọc mấy trao đổi trên mạng thì thấy nhắc tới https://orcid.us.org/no-hu-hb88/ trong lúc câu chuyện đang nói dở, nên cũng tò mò mở ra xem thử cho biết. Mình không tìm hiểu sâu, chỉ xem qua trong thời gian ngắn để nhìn bố cục và cách sắp xếp các mục nội dung tổng thể. Cảm giác là trình bày khá gọn, các phần rõ ràng nên đọc lướt cũng không bị rối, với mình như vậy là đủ để nắm thông tin cơ bản rồi.

Mình có lần lướt đọc mấy trao đổi trên mạng thì thấy nhắc tới https://fun79.ink/mien-tru-trach-nhiem-fun79/ trong lúc câu chuyện đang nói dở, nên cũng tò mò mở ra xem thử cho biết. Mình không tìm hiểu sâu, chỉ xem qua trong thời gian ngắn để quan sát bố cục và cách sắp xếp các mục nội dung liên quan. Cảm giác là trình bày khá gọn, các phần rõ ràng nên đọc lướt cũng không bị rối, với mình như vậy là đủ để nắm thông tin cơ bản rồi.